CAREERS PODCASTS

MARGARET HAGAN

Director, Legal Design Lab, Stanford Law School and d.school

You’re a lawyer and you want to innovate. Where you do you start? Margaret shares a great primer on design thinking, and points to some resources if you’re interested in exploring more.

Resources

She also recommends this handbook

Design Thinking (HBR - subscription required)

Show Notes

|

Mitch: |

Hi, it’s Mitch Zuklie, and I’m thrilled to have as my guest today on the Orrick podcast my good friend Margaret Hagan, who is the Director of the Legal Design Lab at Stanford. Margaret, do you want to describe a little about what the Design Lab does? |

|

Margaret: |

The Design Lab at the law school at Stanford is basically an R&D group. We have law students, fellows, staff like myself and faculty from across the University that are affiliated. And we work directly with legal organizations—law firms, legal aid groups, courts, legal aid funders—to be a sandbox for new ideas, to work with them on bringing innovation into their organizations, and then also—especially in the access to justice space—building new applications and testing them. |

|

Mitch: |

For those listeners who are new to the concept of design thinking, can you tell us what that’s all about? |

|

Margaret: |

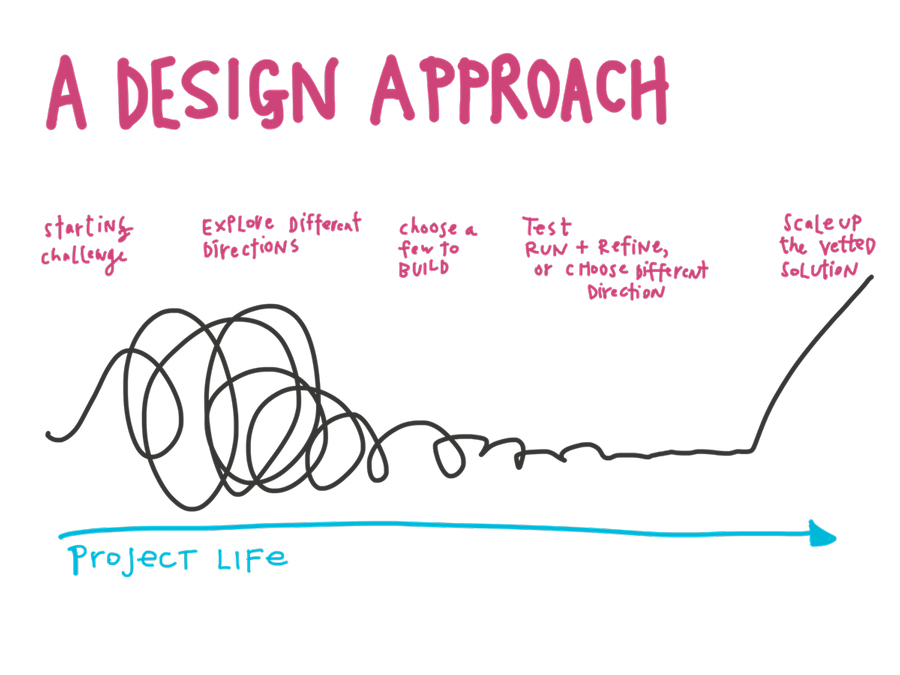

Design thinking… it grew out of this trend, human-centered design, that came from building physical products and then interactive digital services. And then, somewhere in late 90s, early 2000s, this notion of design thinking—how to bring those methods for innovation out of more consumer products into financial services, medical services, also legal services—sprung up. |

|

Mitch: |

Now, you had a passion, as I understand it, about access to justice, as well as design thinking since your days back at Stanford. How did you find your way to this incredible career? |

|

Margaret: |

My third year of law school, I was in a class called Legal Informatics, so all about technology and information systems. I was in Ethics, taking my mandatory Ethics class with Deborah Rhode, talking a lot about the access to justice crisis, and I was in a design school class—taught by now Justice Cuéllar in the design school—that was on design for refugees. And the methodology of the refugee design class, where we were working directly with the UN about new ways to get education and communication into refugee camps, mixed with the legal informatics, studying all these new start-ups that were cropping up, new technologies, and then the ethics class. It just was stewing around in my head: Can we use those methods, along with the technology, on this crisis? Then I had the fortune, after I graduated from law school, to have a year—basically an incubation year at Stanford design school—where I had a year to figure out how to bring design methodologies to the world of law, and started building these partnerships with the courts, with self-help centers, with legal aid groups. That then blossomed into this proper lab that I direct now. |

|

Mitch: |

I’m curious what advice you’d have for our listeners about how to bring more innovation into their day-to-day work lives, whether that’s in the law, whether that’s doing community work, or whether it’s in some other area they’re interested in. How do you think about bringing innovation to what one does? |

|

Margaret: |

So, we tend to think about how we can re-frame our frustrations that we know very well—what takes too long, what’s inefficient, what’s annoying—how to reframe those into design opportunities. And it’s about figuring out—whether it’s yourself who’s the person experiencing those frustrations, or people on the other side of a transaction or a service you’re providing—who might be frustrated and have some needs. Thinking more systematically about what those are, what’s going wrong now, and where there’s ways that innovation can be brought in. And then we try to frame those into basically brainstorming jumping-off points, design opportunities, where we think within the constraints that we have—whether it’s budget or technology or staffing—what are different ways that we could serve these people? So really adopting this mindset of, “How can we be of service to the people at the center of the problem?” And then it’s a matter of, given those constraints, what are innovations? So, innovations can be new ways of presenting information, it could be new technology to build, it could be new services or organizations or roles. |

|

Mitch: |

Margaret, would it be fair to say then that it’s a little bit like the Jony Ive approach of taking something that’s ugly and making it beautiful? Is that a fair simplification? |

|

Margaret: |

There’s definitely—the beauty factor is definitely there. We tend to use the metrics of engagement. |

|

Mitch: |

Yeah. |

|

Margaret: |

So, not even just does it look nice, but does it make that person, that audience or that user you’re targeting… does it spark their interest, does it help them become the person they want to be, is it really useful fundamentally to them? That’s always the metric that we’re aiming for. |

|

Mitch: |

Right. I’d be curious: If you looked at the design process, you know, from start to finish, what percent of the total time that you and your colleagues spend working on design innovation is actually listening to other people? |

|

Margaret: |

We invest in that a lot. So when we have the luxury to do a big, proper design process through a class, we spend the first four weeks without getting to any solution… where it’s just about hearing from as many stakeholders as possible. And we do that in a lot of different ways, it’s not just all interviews. We do a lot of observations, we do a lot of what we call “service safaris” where we just observe people in the wild—at a court, in a self-help center, in a legal aid office—or where we go along with them, kind of over-the-shoulder. But we try to combat that tendency of lawyers, which is to try to solve the problem as soon as you hear— a framing of it. But instead really understand the experience, try to synthesize that information and then jump to making—but even in that making, we try to still be testing almost every week, whatever we’re coming up with, to go back to the stakeholders and say, “Is this on track? Would you actually use this?” |

|

Mitch: |

If you had a magic wand, in terms of changing something about the legal education system to enable students to be better prepared to think this way and to apply design standards to the way they approach legal problems, what would that, you know, magic wand render? |

|

Margaret: |

I almost wish for every 2L or 3L that is going into a law firm or a public service organization, that they could work—the year before they actually start the job there—on an innovation problem of that firm or that organization, where they can know better about how those organizations actually operate and start to basically design the better workplace for themselves, at the same time as really understanding what they’re about to get into. I say that actually informally a lot with my students, that they are still—they think of themselves at the bottom of the hierarchy in law school, but through the classes they are able to talk to managing partners, to justices of the court, to all kinds of other leaders, and they really get to understand the mechanics and the profitability and the structures of these organizations, and they start to take ownership of their career, and I think they can go in with a lot more leadership skills into these organizations. |

|

Mitch: |

With that grounding. |

|

Margaret: |

Yeah. |

|

Mitch: |

If we had a listener that was very interested and thinking about—a student, for example, but not at Stanford, someone who’s not in the Margaret orbit—what would you recommend that he or she reads, or how do you recommend that he or she gets better connected with design thinking and finds opportunities in their own environment to get some glimpse into the areas that you specialize in? |

|

Margaret: |

Sure. There’s a lot to read online. Just, if you go into the world of medium, medium.com, where there’s just lots of designers and technologists on there sharing their best practices, their case studies… it’s the most lively community. For kind of good, solid background reading, I’d recommend Tim Brown’s Harvard Business Review article just called “Design Thinking.” It gives about six pages with some case studies—very solid. There’s a lot of other more handbook-like things; if you’re ever interested in actually running a design workshop or even doing it with yourself, there’s a great handbook from the LUMA Institute called “Human-Friendly Innovation”… “Designing for Humans”—I can’t remember the title but highly recommended. |

|

Mitch: |

How about your own website? |

|

Margaret: |

Sure. Yeah, so, come on over to Legal Design Lab at legaltechdesign.com, where I have my running blog where I have lots of illustrations about all the conferences I go to. That’s called openlawlab.com. Lots of stuff on legal design there. |

|

Mitch: |

Is there a question that I’ve failed to ask that you wish that I had? |

|

Margaret: |

Hmm. {laughter} Can I ask you a question? |

|

Mitch: |

Yeah, fire away. |

|

Margaret: |

So, as a leader within the law firm world, do you see that there’s new opportunities for graduating law students to have a job that lets them do innovation work at the same time as more traditional legal services work? |

|

Mitch: |

Yeah, absolutely. And I think that—let me say a couple things. The first is that client demand for innovation is very powerful. I think, equally importantly, I think that all of us who strive to do a great job for our clients are hungry to do that in our own right and think it’s an important part of delivering better value every day. So I’d also say that, in that world, there’s more of a premium—I know that we put more of a premium everyday on hiring folks who’ve got good evidence of having worked in teams prior to coming to join us. Doesn’t mean they have to have had extensive work experience in the team setting, but some evidence that they’re able to work in teams. Because—it’s always been a team sport—but, increasingly, the delivery of legal services requires you to work, not only with other lawyers and staff members, but also this broader array of people with different skills sets; and therefore, people who have got a demonstrated interest facility history of working in broad teams tend to be the most successful people that we bring to the organization. So I think that means that there will only be more and more demand for Margarets, uh… |

|

Margaret: |

That’s great. |

|

Mitch: |

…in the world. |

|

Margaret: |

I’m glad to hear it. |

|

Mitch: |

Margaret, thank you so much for spending time with us. Total pleasure. |

|

Margaret: |

Thanks, Mitch. |

- Orrick is an AA/Equal Opportunity Employer

- Disability and Reasonable Accommodations

- EEO Statement

- E-Verify

- Right to Work

Please read before sending e-mail.

Please do not include any confidential, secret or otherwise sensitive information concerning any potential or actual legal matter in this e-mail message. Unsolicited e-mails do not create an attorney-client relationship and confidential or secret information included in such e-mails cannot be protected from disclosure. Orrick does not have a duty or a legal obligation to keep confidential any information that you provide to us. Also, please note that our attorneys do not seek to practice law in any jurisdiction in which they are not properly authorized to do so.

By clicking "OK" below, you understand and agree that Orrick will have no duty to keep confidential any information you provide.