The Fundamentals of the Unified Patent Court System and the New Unitary Patent

February.01.2022

For further insights related to the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court click here.

To understand the impact of the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court, it is helpful to consider the status quo of European patent law.

Each European country has its own patent laws, and patents are generally granted with national effect only.

Example: To protect an invention in Germany, France and Italy, one needs to obtain one patent in Germany, one patent in France and one patent in Italy. Each of those patents must be separately enforced—and can only be separately challenged—before the respective national courts.

There are two routes for obtaining patent protection in Europe. One can either apply for national patents with the respective national patent offices (directly or via a PCT application), or one can file an application for a so-called European Patent with the European Patent Office (EPO).

Contrary to what its name suggests, the European Patent is not a patent with effect for all of Europe. It is effectively a bundle application that allows applicants to obtain patent protection through a single application in up to 38 European countries that have acceded to the European Patent Convention. However, once the EPO has granted a European Patent, the bundle application effectively falls apart into identical but entirely independent national patents which, again, have to be separately enforced and can only be separately challenged before the respective national courts.

This is where the Unitary Patent and the Unified Patent Court come in. We will address both in turn.

1. The Unitary Patent

1.1. What is the Unitary Patent?

The Unitary Patent—the official name is "European Patent with Unitary Effect"—is effectively a European Patent that is designated to count as a single patent covering all of the participating EU member states. In particular, this means that:

- it provides uniform protection and has equal effect in all of those member states; and

- it may only be limited, transferred or revoked, or lapse in respect of all of those member states.

The procedure for obtaining a Unitary Patent will be fairly straightforward: File an application for a "classic" European Patent with the EPO as you would today. Within one month from the publication of grant of the European Patent, file a request for unitary protection with the EPO. No further national validations or translations into the official languages of the respective member states will be required.

The request for unitary protection can only be filed for European Patents that are granted on or after the date on which the UPC goes live. It will not be possible to retroactively transform previously granted European Patents into Unitary Patents.

1.2. Will the Unitary Patent replace the traditional European Patent and/or national patents?

No, the Unitary Patent will be an additional option existing side-by-side with traditional European and national patents. Both European Patents and national patents will continue to be available and remain in force. Applicants will be free to decide which route to pursue for obtaining patent protection in Europe.

1.3. Will the Unitary Patent afford patent protection for all of Europe?

No, that would be way too simple a system by European standards.

First, the Unitary Patent system is presently open to EU member states only. Other European countries cannot participate even if they partake in the "traditional" European Patent system established by the European Patent Organisation (e.g., the United Kingdom or Switzerland).

Second, EU member states are not automatically part of the Unitary Patent system but are free to join or not to join. Some EU member states have decided not to join at all while others have indicated their intention to join but have—deliberately—not yet completed the requisite process.

Therefore, only certain EU member states, including, however, major markets like Germany, France and Italy, will participate in the Unitary Patent system. The Unitary Patent will be effective only in those countries which are officially referred to as the Contracting Member States (CMS).

The following graphic illustrates the status quo at the time of writing:

1.4. How much will a Unitary Patent cost?

At the time of writing, the annual renewal fees for a Unitary Patent are EUR 35 in year 1, gradually increasing to approximately EUR 1,200 in year 10 and approximately EUR 4,900 in year 20, resulting in a total of approximately EUR 35,000 over the full 20 years patent term.

This roughly corresponds to the cumulative fees for a classic European Patent covering the four European countries with the most European Patent validations in 2015 when the fees were set. In fact, a study published by the European Patent Office here concluded that a Unitary Patent will be more cost efficient than a European Patent covering four or more EU member states, in particular taking into account that—unlike a classic European Patent—a Unitary Patent does not trigger any further costs for national validations and certain translations.

2. The Unified Patent Court

2.1. What actions can be brought before the UPC?

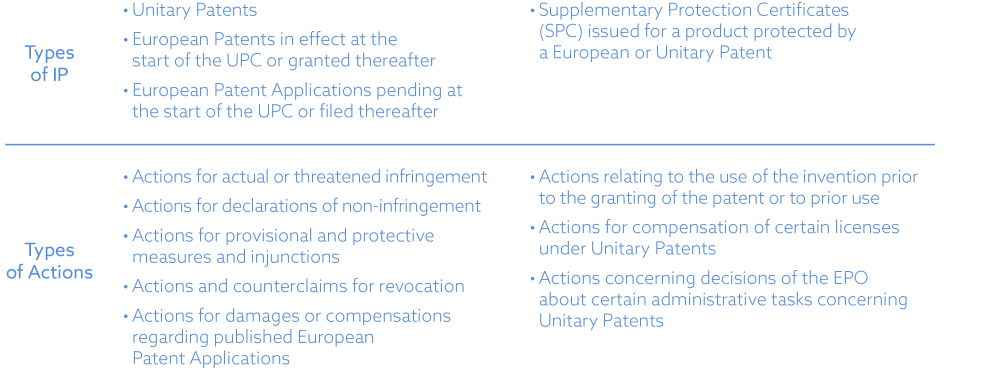

In a nutshell, the Unified Patent Court (UPC) will have exclusive jurisdiction for actions concerning the infringement or revocation of Unitary Patents and European Patents validated in Contracting Member States (i.e., EU member states participating in the Unitary Patent system).

The below table gives the complete picture, listing the types of IP and actions that the UPC will be competent for.

2.2. What is the difference between a UPC judgment and a judgment by a national court?

Decisions of the UPC will have uniform effect in all Contracting Member States. In particular, it will be possible to enforce or invalidate European Patents in a single proceeding with uniform effect in all of the Contracting Member States for which they were granted.

Example: Company A owns a European Patent granted for Germany, France and Italy. Company B sells infringing products in those countries. A can file an infringement action with the UPC and—if all goes well for A—obtain an injunction against B that is effective in Germany, France and Italy without having to sue B in each of those jurisdictions. Conversely, B could file a single invalidity action with the UPC against A's European Patent to have the patent revoked in all three countries.

Similarly, Unitary Patents can be enforced or invalidated with effect in all Contracting Member States through a single proceeding at the UPC.

2.3. Will all disputes concerning European Patents be handled by the UPC?

No, again, that solution would be way too simple by European standards.

First, at the time of writing, only a subset of EU member states, the Contracting Member States, will participate in the UPC (see section 1.3). The UPC will have jurisdiction over European Patents only in those CMS. If a European Patent is (also) validated in a non-CMS, it cannot be enforced or revoked at the UPC with effect for that country.

Example: Company A has a European Patent that is validated in Germany, France, the UK and Spain. Company B infringes the patent in all four countries. Company A can file an infringement action at the UPC with respect to Germany and France only, because the UK and Spain are not participating in the UPC. Similarly, Company B could challenge the patent's validity at the UPC with respect to Germany and France only.

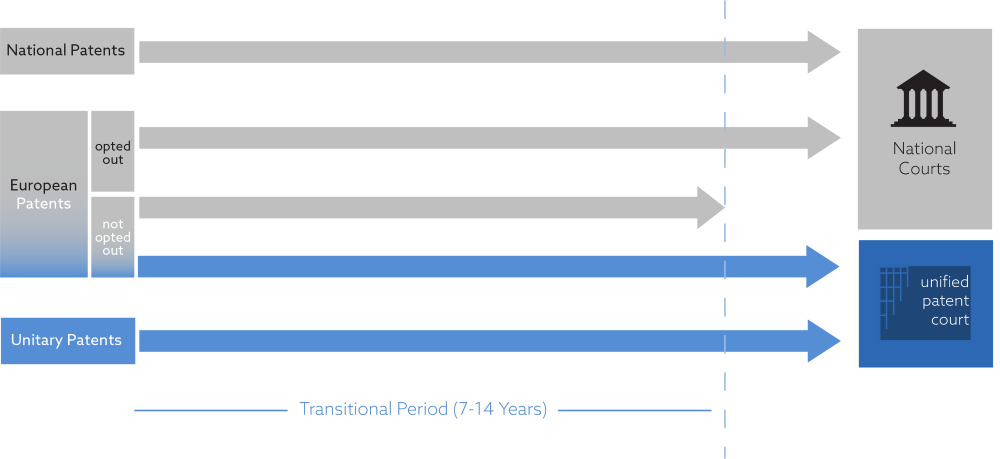

Second, there will be a so-called Transitional Period of at least seven years. During the Transitional Period, claimants will be able to choose whether to enforce or revoke a European Patent at the UPC or on a country-by-country basis at the national courts.

Example: Company A has a European Patent that is validated in Germany and France. Company B is infringing the patent in both countries. Company A can decide whether to file a single infringement action with the UPC or separate infringement actions with the German and French courts, respectively. Similarly, Company B could choose between seeking to revoke the patent through a single action at the UPC or through separate national proceedings in Germany and France.

Third, patentees can opt-out their European Patents from the jurisdiction of the UPC. Upon opt-out, the UPC will not have any jurisdiction over the relevant European Patent and its national validations. However, an opt-out will only be possible until the end of the transitional period and only for as long as the relevant patent has not yet been the subject of proceedings before the UPC. We will address the timing, procedure and pros & cons of opting out in more detail in a separate post.

Finally, the national courts will retain exclusive jurisdiction over disputes concerning European Patents as an item of property (e.g., ownership issues).

The following graphic illustrates the basic concept:

2.4. What is the structure of the UPC?

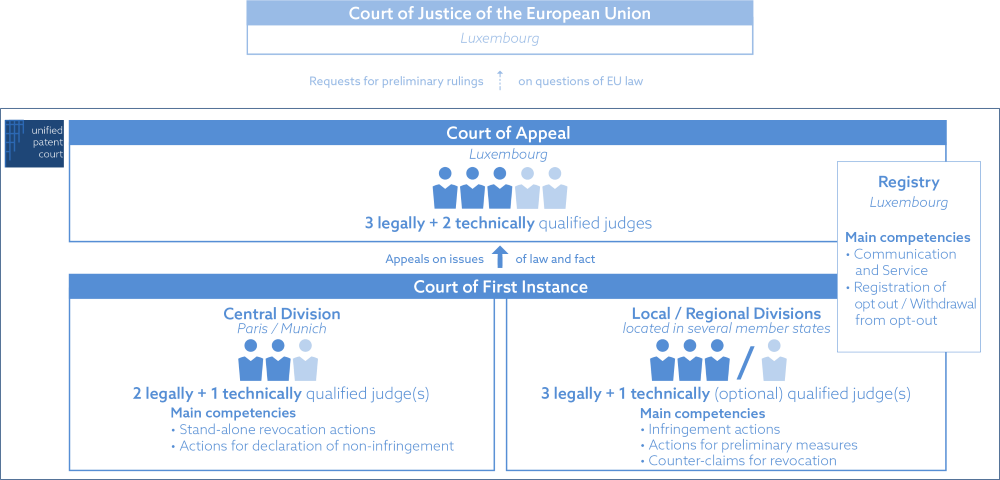

The UPC will have two instances: the Court of First Instance and the Court of Appeal.

The Court of First Instance is comprised of one Central Division and several Local Divisions and Regional Divisions.

- Central Division: The Central Division has its seat in Paris and a section in Munich. It will be the forum for, in particular, stand-alone revocations actions and actions of non-infringement. In some cases, it will also serve as an optional or fall-back forum for hearing infringement cases. Its judicial panels will be composed of two legally qualified judges from different member states and one technically qualified judge.

- Local Divisions: Local Divisions will be the default forums for most infringement actions and counterclaims for revocation can be established in each of the participating EU member states. Each Contracting Member State may set up between one and four Local Divisions depending on the number of patent cases pending in that state. Germany, for example, will have four local divisions in Dusseldorf, Hamburg, Mannheim and Munich, respectively. At the time of writing, the other Contracting Member States are expected to have no more than one Local Division each. At the Local Divisions, cases will be heard by a panel of three legally qualified judges, at least one of whom must be from another member state. Upon request of the parties or the panel, a technically qualified fourth judge will supplement the panel.

- Regional Divisions: Regional Divisions can be set up for two or more participating EU member states and will, effectively, serve as a shared Local Division for the relevant Contracting Member States. At the time of writing, Sweden, Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia have announced that they will share a Regional Division seated in Stockholm. As with the Local Divisions, the judicial panels hearing the case will consist of three legally qualified judges and, optionally, a technically qualified fourth judge.

The Court of Appeal has its seat in Luxembourg. Cases will be heard by a panel of three legally qualified judges from different member states and two technically qualified judges.

Incidentally, as any other court of an EU member state, the UPC will have to refer questions on the application of EU law to the Court of Justice of the European Union for a preliminary ruling.

The following graphic illustrates the basic structure:

2.5. Will the UPC really go live at the beginning of 2023?

It seems very likely at least. Granted, it is hard to count the many times the UPC was supposed to be coming "soon" or "next year" but then never came. However, there are at least two good reasons to believe that this time will be different:

- First, 19 January 2022 marked the start of the provisional application period (PAP) of the Unified Patent Court Agreement. The PAP enables the final technical preparations to ensure that the UPC will actually be operational when it opens its gates. Amongst others, the start of the PAP confirms that there is strong political support among the Contracting Member States to finally start the Unitary Patent system.

- Second, it seems like the two major roadblocks delaying the UPC over the past several years have been more or less cleared: Brexit has been implemented and the UK has formally withdrawn its bid for participation in the UPC. Furthermore, the German Constitutional Court indicated in a preliminary ruling that the constitutional complaint filed against Germany's UPCA implementation act was manifestly without merit (caveat: the main proceedings are still formally pending) which allowed Germany to proceed with the ratification process. In fact, the only remaining legal step for the Unitary Patent system to go live is now the formal deposit of Germany's deed of ratification.

The UPC Preparatory Committee expects that the final technical preparations will take about eight months to complete. Germany is expected to deposit its instrument of ratification once those preparations are complete. This will then trigger a three-month sunrise period after which the Unitary Patent system will automatically go live. All in all, this adds up to 11-12 months from now until the go-live date.